Scientific Expedition // 2018

Surveying the Late Devonian Mass Extinction in Mongolia

Connecting the dots on climate change through the Late Devonian Mass extinctions

Introduction

In 2018, I accompanied a team of geologists and researchers to the Gobi-Altai desert. Their research into the late Devonian mass extinctions more than 350 million years ago has many implications on our understanding of how climate change is affecting ecosystems across the planet now.

In partnership with The Explorer’s Club and The National Geographic Society, I was afforded the opportunity to photograph these heroes of science, and help fulfill one of my goals: to elevate the standing of scientists and explorers through photography.

The Team

A small group from Appalachian State University

set out to study, document, and catalogue geological findings from the Late Devonian Period. With colleagues from the Institute of Paleontology and Geology, Mongolian Academy of Science, the team spent several weeks in the remote region of the Gobi-Altai Desert.

Left to right: Johnny Waters, Allison Dombrowski, Sersmaa Gonchigdorj, Will Waters, Sarah Carmichael (holding @the_explorers_club flag) Peter Koenigshof and Olivia Paschall

Left to right: Otgonbaatar Dorjsuren, Otgonbayar Nerkjhav, Tumurchudur Choimbol, Ariunchimeg Yarinpil & Ganbayar Gunchinbat.

The Campsite

After several days of arduous travel by plane and off-roading SUVs, we found ourselves nestled in a verdant valley situated between the Gobi Desert and the Altai Mountain range. From our campsite, the desert and undulating hills seemed to fade infinitely into the horizon–a truly humbling feeling. The scale and remoteness of the place felt alien, and it was here that we would set up camp for three weeks.

The Field Site

The area you see here was at the shore near an ancient volcano. Over the millennia it was mostly under water, but also sometimes exposed to the elements, and has shifted onto its side through tectonic plate movements. Perfect conditions for Geologists to study! This ‘section’ has a varied history, perfect for learning about how life on earth changed as time progressed.

365 million years ago (roughly)…

This area was teeming with life, but as organisms die their bodies, along with soot & ash from volcanic eruptions, sink to the bottom of the ocean and fossilize into distinct layers over time. The area you can see below represents several millions of years of deposits.

Notice the distinct layer of lighter color material running down from the two geologists in the light blue? We’ll get back to that later…

It is rare to find such a perfectly preserved record of our planet’s history. The arid conditions and remote location of the site helped preserve this geological marvel for eons.

The white bags you can see snaking away behind our lead stratigrapher (definition at bottom of this page) Peter Königshof are ‘sample bags’ in which rock and fossil samples are collected from each layer. These are then studied down to the microscopic level in laboratories around the world.

Mapping by Kilometer

This ‘section’ forms only a small part of the larger picture of what happened in this area around 365 millions years ago. As we are looking at the effect that a nearby volcano had on creating the mass extinction, it was important to understand the geological make up of the surrounding region. Imagine standing in Times Square and trying to get a sense of what it would have looked like 100 years ago. Here we do that for 100s of millions of years in the past!

To do this, the team trecked on foot up and down the surrounding mountains and the valleys (and in the process also scouted the fantastic shoot locations I ended up using for the individual portraits).

Ariuna Yarinpil on location

Ariuna collects fossil sample from the southern flank of the research area.

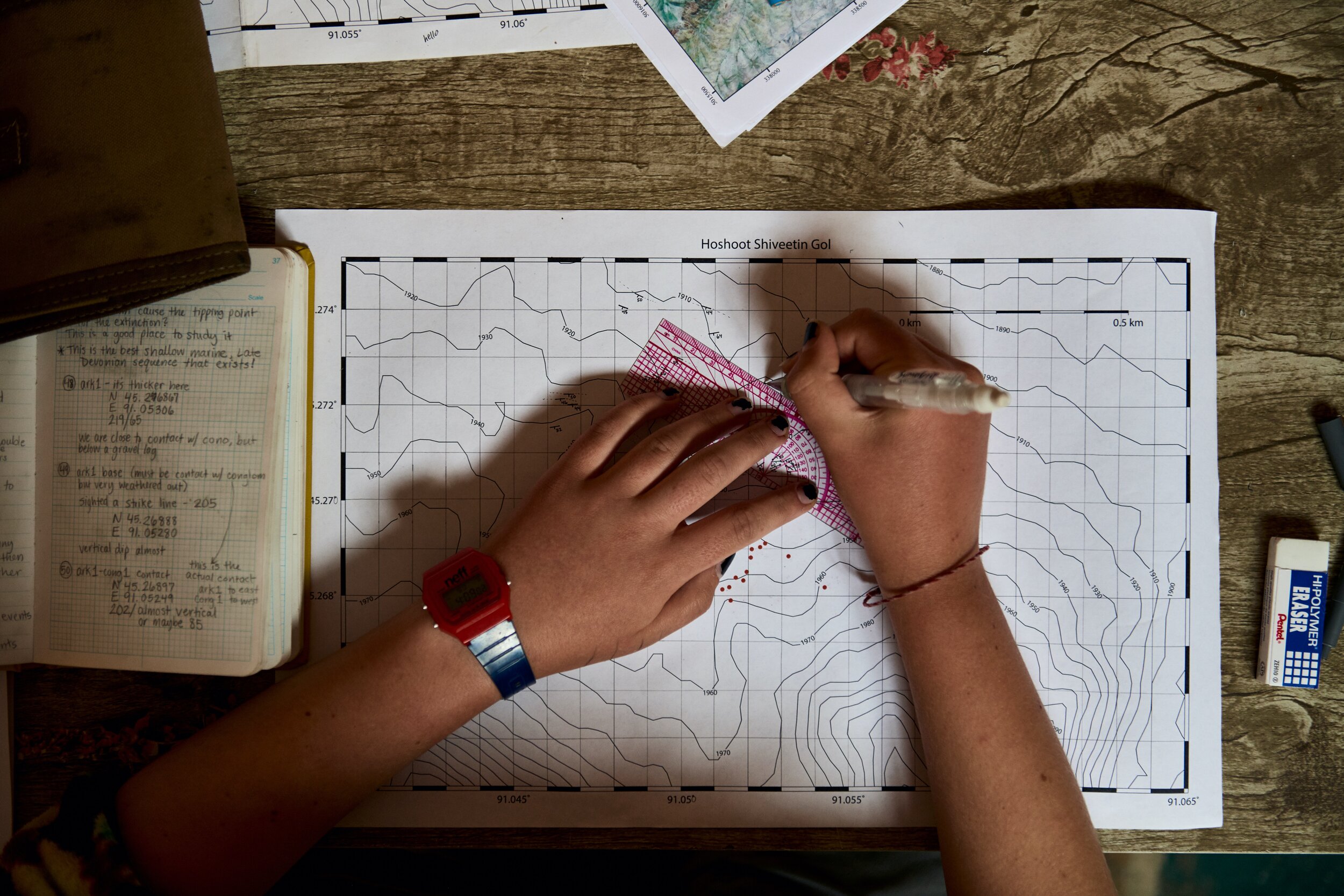

The team working on large scale maps of the field area

walking the ridges with our home base in view

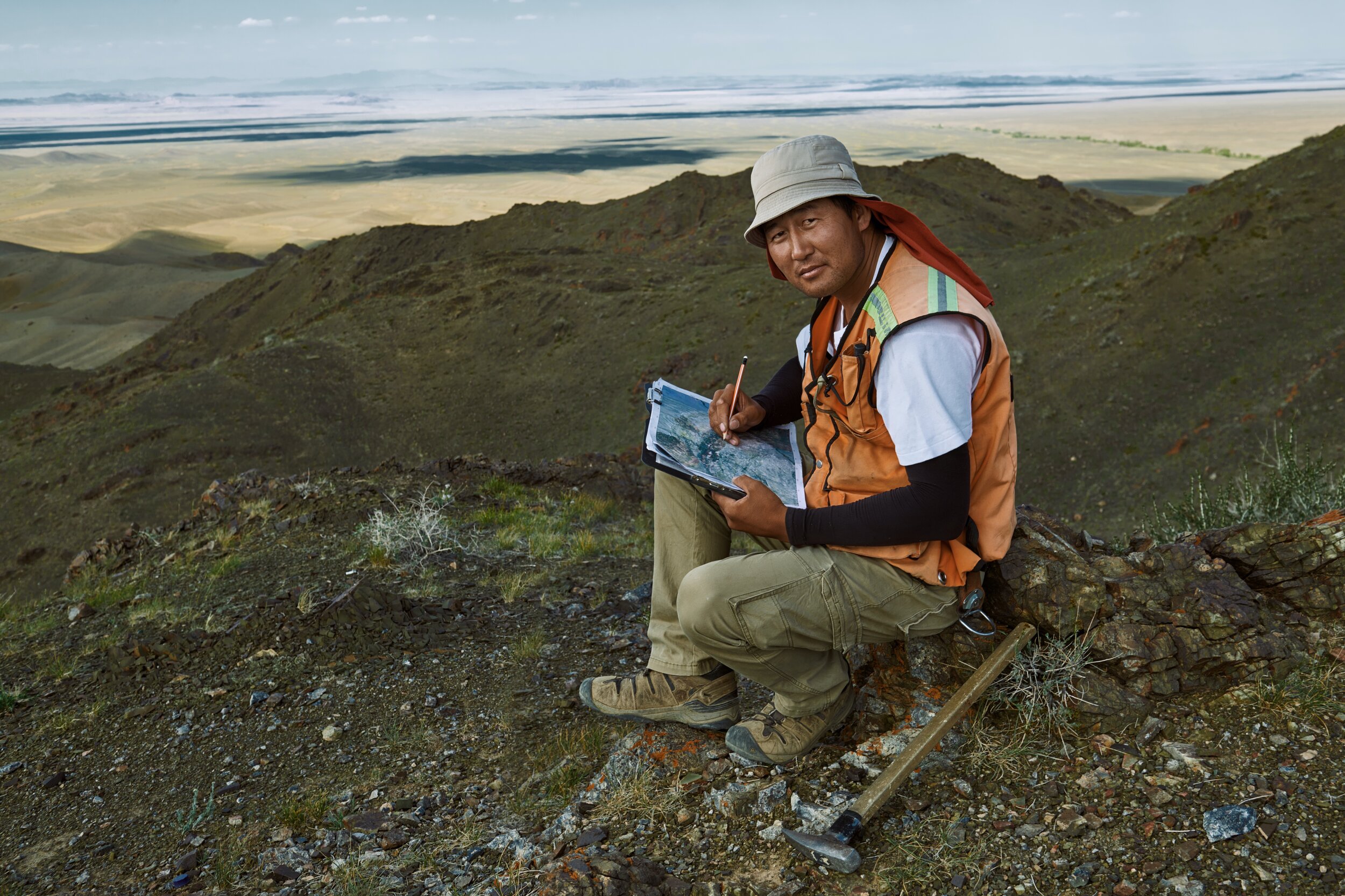

Otgonbaatar Dorjsuren, large scale mapping team, in the foothills of the Altai Mountains, with the plains of the Gobi desert in the background.

Ganbayar Gunchinbat inspects a fossil

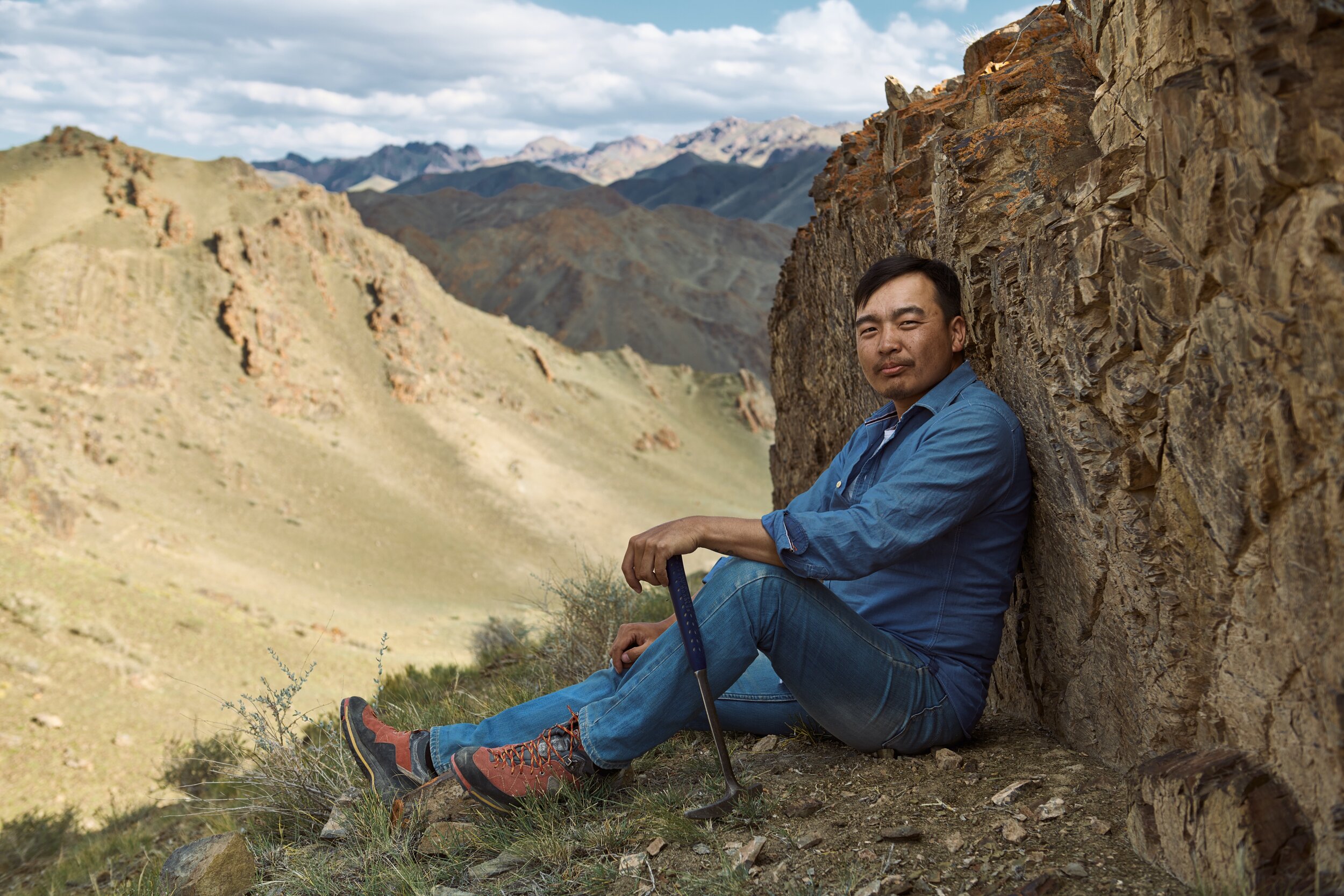

Otgonbayar Nerkjhav

Tumurchudur Choimbol

The team reviews their maps

Ganbayar Gunchinbat

Ganbayar Gunchinbat & Sersmaa Gonchigdorj review maps back at one of the Gers we had set up as offices and field work sites.

The team reviews their work with the other mapping teams

Mapping by Meter

Over time, Geological processes have the power to transform a landscape. For example, seasonal mountain runoff deposits new material over a fairly short period of time. To understand the rough age and layout of a section, it is necessary to walk and take a meter by meter reading of the surrounding area.

If the kilometer mapping is done by climbing a hill and looking out from it’s apex, meter mapping is done by walking around and kicking rocks.

Sarah Carmichael - expedition lead and Professor of Geology at Appalachian State University

This involves a lot (A LOT) of detailed maps.

As a non-geologist, it's fascinating to see how they can pick out details in the landscape that I would never notice. This is why this scale of mapping is so important - seeing how each layer (strata) of deposit has moved over time.

Olivia Paschall

Sarah was joined by Olivia Paschall in this work, seen here with Ariuna surveying the valleys near the core of the field site.

Sarah's team worked closely with the kilometer mapping team to help get a solid sense of the meter to meter makeup of the geology of the area we were exploring.

Detailed mapping by Olivia

A drone's eye view of the field site, clearly showing the features of the area. Notice, for example the river bed (in pale blue) on the right, and the soil deposits at the bottom of each valley. Those are much more recent than the field site itself. Many fascinating geological marvels are simply buried under more recent deposits, which makes our field site even more unique, considering how old it is. Notice also the dark spot near where the vehicles are parked? That's a wildstock feed area, with lots of fresh 'deposits'.

Sarah in the field

Mapping by Centimeter

At this scale, almost all of a geologists work is done in the classic squat pose. A real challenge for a portrait photographer, you really start to get a ‘down to the ground’ perspective of the work. The centimeter work is done close to the ground, doing a thorough forensic analysis of each layer of deposit (strata). This is the real meat and potatoes of the work.

Each layer is sampled and will be transported to a lab for chemical analysis. This is the work that shows gives us a concrete sense of how deposits changed over time.

This is where you find out, for example, that a species of algae may have taken over an ecosystem, or that a species of choral has gone extinct.

Led by Sersmaa Gonchigdorj and Peter Koenigshof, the centimeter mapping team had the most interesting (to me) job of all, digging through each strata to unravel the mysteries laid down by time.

Led by Sersmaa Gonchigdorj and Peter Koenigshof, the centimeter mapping team had the most interesting (to me) job of all, digging through each strata to unravel the mysteries laid down by time.

They were joined in the work by research student Allison Dombrowski

Peter and Sersmaa and Allison in the field

Their work entailed meticulous sampling and analysis of every single strata along the site.

Samples are collected from every significant strata.

Over time, the puzzle comes together. The aim is to form a complete understanding of each layer of deposit.

Tools of the trade: Moisture wicking socks are a must.

hammers, tape measure....

sample bags...

and plenty of note books.

A shovel is a useful tool for removing top soil and really get to the OLD deposits.

It is back-breaking work.

But the reward is worth it. Here's Peter with just a fraction of the samples collected, ready to be analyzed in the lab.

The Fossils

Fossils are the key to unlocking the whole mystery. The final piece that puts the puzzle together. Father and son team Johnny and Will Waters took charge of this meticulous work. Without them, there’s really no way to know about species loss.

It was fascinating to see them work and identify species, and seeing how these ancient organisms have evolved over time, and seeing fossils of species that don’t exist anymore at all.

It’s All About the Algae

The Algae tells the whole story.

But first, remember when I told you to pay attention to the layer of lighter material?

Eagle-eyed observers will see that there’s a couple other thinner layers of the same, left of the big strip. Every one of these light-colored stripes was a volcanic eruption, spanning many years, each pushing the ecosystem to the brink, but never causing a mass extinction. Until the big, thick layer of Ash that’s so clearly visible even from a drone shot…

We know the Devonian Mass Extinction happened over millennia, but there was one main event. Until now it had never been clearly defined.

The algae give us a huge clue. While the fossil record shows that diversity was decreasing throughout the period, the biggest change came after a huge layer of algal deposits.

We’ve all heard of an ‘Algal Bloom’, when Algae takes over and grows at an exponential pace in the ocean. It happens when ecosystems collapse and Algae takes advantage of what’s left.

Because the Algae has few predators and feeds on all the nutrients and oxygen in the ocean, it causes all other species to literally choke, causing an extinction.

All those millions of years ago, there was very little land-based life, and most species lived in the oceans. This is why the Devonian Mass Extinction, which caused death in the oceans, had such an effect on all life on earth.

Why it Matters

The conditions created by the Algal bloom is called Anoxia which literally means ‘no oxygen’.

Anoxia is happening again in our oceans. These days fertilizer run-off from farming, as well as ecosystem collapse, algal blooms and other factors cause Ocean anoxia in regions across the planet. These can have huge effects as our planet’s climate changes.

In the fossil record in Mongolia, there’s proof of many small extinction events, which eventually resulted in a catastrophic collapse of the ecosystem.

It is important to learn lessons from the past, and this research into the Devonian Mass Extinction give us important clues about how man-made climate change is playing out.

The Local People

High above our home base, tucked into the valleys near the Chinese border, lives a couple of military families. They agreed to let me photograph them a couple of times, including portraits with the camels onto which one of them was loading their belongings, ready to move to a new spot.